PFAS at the former Fort Ord

By Pat Elder

March 27, 2025 - 52 pages

An artist’s rendition of perfluoro octane sulfonic acid, (PFOS), (C₈F₁₇SO₃H). This is one compound among 16,000 types of per-and poly fluoroalkyl substances, (PFAS).

The former Fort Ord is plagued with PFOS.

Summary

The Army has identified seven locations on the former Fort Ord base that are seriously contaminated with per-and poly fluoroalkyl substances, (PFAS). These toxic “forever chemicals” were used in a host of applications and products and they remain in the environment. The sites include landfills, a waste treatment plant, a burn pit, and hangars at the Marina Municipal Airport. They are owned by the Army, the state of California, and the cites of Seaside and Marina. The contamination presents an ongoing threat to human health.

The Army initially identified 61 sites with potential PFAS contamination. They whittled it down to 42 sites and they reduced that number to 10 sites. They finally settled on seven areas to examine.

The human carcinogens were used and discarded at multiple areas on the former base while there are more locations where the chemicals were likely used. The Army devised a scheme to convince the public that the threat posed by these carcinogens is minimal. Thousands of contaminated acres of land have been conveyed to largely unsuspecting civilians.

The Army’s chief talking point is that there’s no risk to human health if people don’t drink water from the PFAS-contaminated A-Aquifer, which extends down 180 feet below the ground at the former Fort Ord. There are multiple pathways to human ingestion the Army fails to address.

The Seaside Campus Town Center is being constructed over an extraordinarily contaminated area, including a burn pit and fire station with dangerous levels of the toxins present in the soil and groundwater. Construction workers and people who live, work, or shop nearby may be in jeopardy.

The Army has failed to examine the propensity of PFAS to become airborne by attaching to tiny soil particles that are lifted by the wind and settle in our lungs and in our homes as dust. They have also failed to produce test results analyzing a suite of PFAS chemicals that are known to volatilize. The Army downplays the exposure from skin contact with soil in lawns and gardens. In addition, the Army has eliminated the potential for surface waters to provide a pathway to human ingestion.

This report examines areas that are believed to be highly contaminated, like the former soil testing area that is located on land now occupied by the California State University, Monterey Bay Campus. Other areas include an Army fire training area off of Numa Watson Road near the Chartwell School. The Fort Ord Nature Reserve is also contaminated with these toxins. We’ll examine how injection wells and basins don’t work well for PFAS.

The Army failed to fully disclose information on five separate fire suppression systems in hangars that were fitted with PFAS foams. These systems have been known to frequently malfunction, spilling vast quantities of carcinogenic foams.

We will report on a massive fire involving tires at the landfill and how it was extinguished using aqueous film-forming foam. Another accident involved up to 10,000 gallons of fuel that spilled at the former Fritzsche Army Airfield, now Marina Municipal Airport. The Army applied PFAS-laden foams to guard against the possibility of fire.

The Army could not define how PFAS is “treated” of “remediated” and that’s because science is still searching for ways to achieve these goals. Generally, the Army excavated areas with known PFAS concentrations and spread them in various locations throughout the base.

This report will examine the concept of vapor intrusion. The DoD and the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry have not performed vapor intrusion studies and/or a review of “Volatilization to the Indoor Air Pathways” (VIAP) inside residential homes at Fort Ord. This is most alarming because of the existence of multiple groundwater plumes with deadly concentrations of volatile organic compounds and PFAS.

The Army also ignored the likely use of PFAS as an aerosol suppressant in chrome plating baths containing Chromium VI, a deadly human carcinogen. This chemical is often found at Army burn pits, along with volatile organic compounds like Benzene and Toluene. Lead, Mercury, Cadmium, and Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) may be found in the soils.

We’ll examine specific details regarding the Army’s sewage disposal practices and their handling of sewer sludge and liquid effluent. These materials are known to contain high concentrations of PFAS.

We’ll look at the amazing database collected by Army veteran Julie Akey. It describes nearly 1,700 veterans and dependents who were stricken with cancer and diseases as a result of their time spent at Fort Ord.

Finally, we’ll track the recent history of land conveyances and the role played by the Fort Ord Reuse Authority, (FORA). FORA was a governmental agency created in 1994 to oversee the transfer and redevelopment of the former Fort Ord. FORA was responsible for planning, financing, and implementing the transition of the contaminated Army base into civilian use. It ceased to exist in 2020.

Special thanks to Nina Beety of Monterey for her editing. Also, thanks to Mike Weaver of Corral de Tierra, and a dozen others who provided valuable comments.

The work herein is taken largely from professional reports commissioned by the Army and completed by the respected firms Ahtna Global, LLC of Monterey, CA and Arcadis U.S., Inc. of Hanover, Maryland.

Can you help us pay for environmental testing on the former Fort Ord? We want to verify the Army’s claim that there are no remaining radiological, chemical, or biological threats to human health. We need your financial help to take our advocacy to the next level. We have raised $2,600 so far. Our goal is $20,000. Our team will visit in early October, 2025 to take samples. Please help us! See the Fort Ord Contamination website. https://www.fortordcontamination.org/

Figure 6 – Surface Water Overview - Marina Watershed, PFAS Site Inspection Narrative Report - Former Fort Ord, California 3/17/23, Ahtna Global, LLC, Monterey, CA.

The figure above shows seven sites on the former Fort Ord that contain cancer-causing per-and poly fluoroalkyl substances, (PFAS). These areas are seriously contaminated and represent an ongoing threat to human health. The seven sites represent a limited designation of carcinogenic hot spots while there are many more to report.

We’ll examine these and additional PFAS-contaminated sites on base. The Army knows what they’ve done to this land. It’s the same around the world.

The 7 aqueous film-forming foam (AFFF) release areas with their corresponding owners:

Site 2 – Main Garrison Sewage Treatment Plant

(California Department of Parks and Recreation)Operable Unit 2 Fort Ord Landfills

(Army)Main Garrison Fire Station Complex

(City of Seaside)Site 10 – Former Burn Pit

(City of Seaside)Fritzsche Army Airfield Fire Drill Area

(Army)Fritzsche Army Airfield Fire and Rescue Station

(City of Marina)Fritzsche Army Airfield Helicopter defueling area.

(City of Marina)

This report will examine PFAS releases at each of these sites and at other locations where releases are known to have occurred or are likely to have occurred. The Army identified 61 “primary assessment sites” throughout the base where PFAS may have been released into the environment. They are shown in Table 1.

From this list, the Army settled on 42 secondary assessment sites where PFAS was thought to be used. These are shown below.

Preliminary Assessment Narrative Report, September, 2022

It’s a good bet that every one of these locations have experienced releases of these deadly toxins. It’s a big deal because these chemicals sicken and kill people by poisoning the air, food, and water - and they never go away. The Army decided to only concentrate on these sites, and they devised a scheme to convince the public that the threat posed by these carcinogens is minimal.

The Army is selling the notion that there’s no risk to human health if people don’t drink water from the A-Aquifer, which extends down 180 feet below the ground at the former Fort Ord. The Army downplays the threat caused by PFAS in the air and the dust in homes. They are not addressing the threat to surface water or the propensity of the chemicals to poison the food chain.

The term “water” is mentioned 4.138 times in the 14,395-page PFAS site inspection document. The term “dust” is mentioned one time in the text of this document. It says, “The inhalation exposure pathway of PFAS via dust is considered potentially complete in soil.”

The Army says the inhalation pathway to human ingestion is “potentially complete.” What does this mean, exactly? Potential thyroid disease? Potential bladder cancer? Potential birth defects?

When a pathway to human ingestion is described as "potentially complete," it means that all the necessary elements for human exposure to a contaminant are in place, and there is a possible route for the contaminant to be ingested by humans. However, the exposure has not necessarily occurred yet, and it may or may not happen depending on specific circumstances.

A complete exposure pathway consists of the following elements:

Contaminant Source – Check.

Contaminants are released into the environment – Check.

The contaminant moves through water, surface water, soil, or air – Check.

A way where people could come into contact with the contaminant, like water, food, or air. Check.

A way for the contaminant to enter the body. Check.

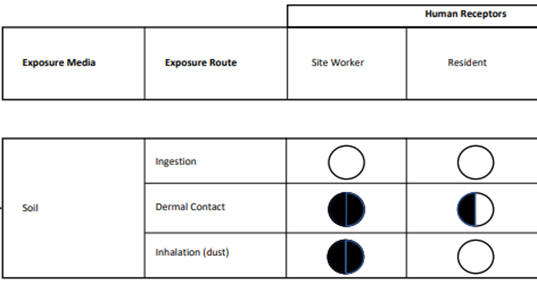

PFAS Site Inspection Report, Figure 27, “Conceptual Site Exposure Model Main Garrison Fire Station”

The Army graphic here shows that inhalation of dust is a complete pathway to human ingestion for site workers, but not to residents. This means the people operating bulldozers and dump trucks in the Campus Town Center may be imperiled. It also means people who work, live, or shop nearby may be in jeopardy.

The Army graphic shows that skin contact with the soil (gardening, etc.) is a partial pathway to human exposure for residents. This exposure entails increased risk of health problems including thyroid disease, bladder cancer, and birth

defects.

The report commissioned by the Army says, “Most of the major PFAS releases of concern at Army installations are likely to contain a variety of PFAS that do not volatilize; therefore, soil vapor and air are not primary media of concern for either transport or receptor exposure and the air pathway was not considered for this site inspection.” We’ll examine the Army’s neglect in analyzing PFAS compounds known to volatilize.

Furthermore, the Army is eliminating the potential for surface waters to provide a pathway to human ingestion. They argue that stormwater runoff from the former Fort Ord to the Monterey Bay or other surface water bodies is unlikely due to the topography and high-infiltration soil types that are present. They say surface water and sediment are not considered potential PFAS exposure pathways for any of the sites and sampling of surface water and sediment was not included in the site inspection.

Surface water on the base is characterized by ephemeral flows of water; that is, streams that flow following a period of rainfall. Locals can tell you that winter storms can produce rain in torrents. Precipitation like that can act like squeezing out a giant toxic sponge that deposits PFAS in the sediment and along the banks of streams. When those areas dry out, the carcinogenic PFAS adheres to tiny soil particles, blown about by the wind, and settles in our lungs and our homes.

See Table 3, Tertiary Assessment Sites

The Army started with 61 sites of potential PFAS contamination and whittled it down to 42 sites where they thought AFFF was used.

The Army then dropped that number to ten sites to be examined in some depth.

However, when the Site Inspection Report on Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances at Fort Ord, California, was released in July, 2023, it left out an analysis of the Ord Village Sewage Treatment Plant, the East Garrison Sewage Treatment Plant, and the Fritzsche Army Airfield Sewer Treatment Plant, leaving only 7 locations to be evaluated. The report went on to identify 17 additional release areas where PFAS releases on the former base are documented, but did not evaluate them.

17 known, but ignored release areas

Range 49, known as the Molotov Cocktail Range, was located approximately 0.5 miles southeast of the intersection of Gigling Road and Seventh Avenue.

Range 40A, designated for Flame Field Expedient training, was located within the Impact Area of the former Fort Ord military base. No further identifying information is available.

Building 4492, known as the Auto Craft Shop, was situated within the 4400/4500 Motor Pool area of the former Fort Ord military base. This area is bounded by Inter-Garrison Road to the north, Gigling Road to the south, 7th Avenue to the west, and 8th Avenue to the east.

The Crescent Bluff Fire Drill Area was located on a bluff approximately three-quarters of a mile southeast of the East Garrison within the former Fort Ord military base. This site consisted of four small fire-fighting training pits.

Range 34, designated as a multi-use range, was located within the Impact Area of the former Fort Ord military base. .No further identifying information is available.

Ord Village Sewage Treatment Plant was located near the beach and served the housing areas near Ord Village.

East Garrison Sewage Treatment Plant was located near the intersection of Reservation Road and Inter-Garrison Road.

Fritzche Army Airfield Sewer Treatment Plant.

Indian Head Beach / Monterey Bay.

Lowlands at the intersection of Lightfighter Drive and General Jim Moore Boulevard.

Low area northeast of the Fritzsche Army Airfield Helicopter Defueling area.

Two infiltration trench areas in the Fort Ord Nature Reserve.

One infiltration basin in the Off-Post Area Armstrong Ranch to the northwest of the Fort Ord Nature Reserve. [location]

Two injection wells in the Fort Ord Nature Reserve.

Soil Conditioner use - Areas throughout the base where PFAS-contaminated “soil conditioners” from the Main Garrison Sewage Treatment Plant (and, likely, the three other treatment plants) were spread. A soil conditioner is a euphemistic term for sewer sludge turned into a marketable commodity in 20 pound bags sold in hardware stores across the country. Bloom’s Soil Conditioner is made of sludge from the Washington, DC Water’s Blue Plains Advanced Wastewater Treatment Plant. It contains 223,000 parts per trillion (ppt) for all PFAS tested, including 23,800 ppt of Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and 22,100 ppt of Perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS), two of the most toxic varieties of PFAS.

Near the Chartwell School Numa Watson Road, south of Normandy Drive.

Fort Ord Soil Testing Area (FOSTA) North of the intersection of Gen. Jim Moore Blvd and Lightfighter Drive.

In addition, there is a lengthy list of areas throughout the base where releases of PFAS very likely occurred. The following 9 sites are of most concern in this classification.

Likely Release Areas

It would be reasonable to find PFAS contamination at the following locations, as PFAS is regularly reported and “remediated” at similar locations on Navy and Air Force military bases. However, the Army is the least transparent of the military branches in this regard.

The idea of “remediating” or “treating” PFAS is not clearly defined in the Army’s discussion of PFAS at Fort Ord and that’s because modern science has not been able to develop universally effective or widely deployed methods aimed at destroying the powerful bond between carbon and fluorine atoms that characterize the myriad of 16,000 PFAS compounds.

All five of the hangars listed below were part of the Fritzsche Army Airfield, which is now Marina Airport. They were all fitted with AFFF fire suppression systems.

Building 507

Building 510

Building 524

Building 527

Building 533

Site 14 - 707th Maintenance Facility occupied the southern half of the area bounded by North-South Road No. 2, North-South Road No. 3, and Gigling Road.

Directorate of Logistics Automotive Yard, containing 8.5 fenced acres east of Highway 1 and northeast of the Southern Pacific Railroad Spur.

RI/FS Site 17 - 1400 Block Motor Pool was located within Fort Ord’s Main Garrison area. This site encompassed the motor pool complex—buildings numbered approximately 1476 through 1495.

IA Site 20 - South Parade Grounds, 3800 Block Motor Pool and 519th Motor Pool. were located in the southern portion of Fort Ord’s Main Garrison.

Magnesium/Teflon/Viton (MTV’s) are pyrotechnic mixtures widely used by the Army, particularly in infrared countermeasure flares designed to protect aircraft from heat-seeking missiles. These compositions can contain up to 45% PFAS. At Fort Ord, flares were utilized during military training exercises for various purposes, including signaling, illumination, and simulation of combat scenarios. (Read more about this use of PFAS.)

We must understand the significance here. Let’s start by examining the seven sites the Army has chosen to closely examine:

Site 2 – Main Garrison Sewage Treatment Plant

Operable Unit 2 Fort Ord Landfills

Main Garrison Fire Station Complex

Site 10 – Former Burn Pit

Fritzsche Army Airfield Fire Drill Area

Fritzsche Army Airfield Fire and Rescue Station

Fritzsche Army Airfield Helicopter defueling area.

Site 2 – Main Garrison Sewage Treatment Plant

The figures here are in parts per billion (ppb). PFOS, with a concentration of 2,800 parts per trillion (ppt) was found a foot down in the sandy soil.

Site 2 is located on the western side of former Fort Ord between State Route 1 and Monterey Bay. The plant is currently inactive. The site had three unlined sewage ponding areas and ten asphalt-lined sludge drying beds, which were demolished and removed in 1997.

The site is approximately 28 acres in size and consists largely of permeable sand dune. The land is currently owned by the California Department of Parks and Recreation. It lies wholly within Fort Ord Dunes State Park, bounded by State Route 1 to the east.

Effluent from the Main Garrison STP was discharged into a storm drain that emptied onto Indian Head Beach during low tide and directly into Monterey Bay during high tide. The sewage sludge was digested anaerobically (without oxygen), dried in asphalt-lined sludge drying beds, and reportedly used as a soil conditioner in various areas across Fort Ord.

No remedial action was proposed for soil contamination at Site 2. However, in 1997, as part of the maintenance and cleanup activities associated with the closure of Site 2, sludge was removed from the drying beds and evaporation ponds. The asphalt-lined drying beds were demolished and about 3 feet of soil was excavated. Approximately 15,000 cubic yards of sludge, soil, asphalt, and wood debris were disposed of in the OU2 Fort Ord Landfills under the engineered cover system.

Although the record does not provide a description of this cover system, these kinds of systems typically consist of multiple layers, including a vegetative layer, protective soil layer, low-permeability barrier (such as a geosynthetic clay liner), drainage layer, and gas venting system.

The Army didn’t address the PFAS contamination; they just moved part of it to the landfill. PFAS never goes away.

Today, the former sewage treatment site area is fenced off, and the site owner and any successors and assigns are prohibited from accessing the groundwater for any purpose. However, groundwater is only part of the problem.

Groundwater from the Main Garrison Sewage Treatment Plant flows northeast, away from Monterey Bay, toward Marina.

The Army sampled four wells in the vicinity, and they all had detections of three or more PFAS substances. The Army says the Upper 180-Foot Aquifer is not used for water supply, and there is no downgradient groundwater use. The term downgradient refers to the direction that groundwater flows. Essentially, it is "downstream" in an underground water system.

The PFAS at this site is not associated with aqueous film-forming foam. Instead, it is the result of the daily discharge of contaminants from hangars and machine shops throughout the Main Garrison. The Main Garrison Sewage Treatment Plant primarily served the Main Garrison area of the installation. This area included the base's administrative offices and housing units. It also included maintenance facilities, and other infrastructure that required wastewater disposal and treatment.

It is instructive to look through the 2023 DOD report, Report on Critical Per-and Polyfluoroalkyl Substance Uses to gain a sense of all the different ways the DOD uses PFAS in products and applications. Certain PFAS compounds that are known to volatilize are likely present in this area. Also, the air is likely to carry carcinogenic PFAS dust. The same is true of the other three wastewater treatment plants not examined in the site inspection by the Army.

Operable Unit 2 Fort Ord Landfills

Landfill Areas B-F are located south of Imjin Parkway. These highly contaminated lands are owned by the Army.

The Operable Unit (OU) Fort Ord Landfills are located east of the Main Garrison area in the north-central part of the former Fort Ord. They are still owned by the Army. Public access is blocked, including with a chain-link fence and signage. The EPA added Fort Ord to the list of Superfund sites in 1990 primarily based on groundwater contamination beneath the Fort Ord Landfills area. It is among the most severely contaminated sites in the country.

Fort Ord Landfills were active from 1955 to 1987 and were used for residential and on-base waste disposal. Area A was used before the advent of AFFF. The OU2 Fort Ord Landfills are currently inactive. The Fort Ord Landfills formerly included six areas: one area north of Imjin Parkway and five areas south of Imjin Parkway, covering approximately 150 acres.

The former Area A Landfill, north of Imjin Parkway, was approximately 33 acres.

Household and on-base commercial refuse, dried sewage sludge, construction debris, and chemical waste were placed in the Fort Ord Landfills.

Additionally, in the 1970s or 1980s, there were at least two fire incidents at the landfill where waste, including tires, burned. AFFF was used to suppress the fire.

From November 15-29, 2022, a total of 13 groundwater samples were collected by Ahtna Global, LLC. All 13 samples had detections of one or more PFAS compounds/substances. Table 11 below shows the results from a sample collected 207.8 feet below the surface, identified as the Upper 180-foot aquifer.

The results of the groundwater investigation indicate there are PFAS compounds in the migration pathway from the Upper 180-Foot Aquifer to the Lower 180-Foot Aquifer which is upgradient of the Marina Coast Water District water supply wells 29, 30, and 31. In other words, the drinking water wells are downstream from the Lower 180-Foot Aquifer.

See Page 54 – Groundwater Conclusions Site Inspection Narrative Report, 2023.

The EPA has established a maximum contaminant level of 4 ppt for PFOS and PFOA. It has also set a maximum contaminant level of 10 ppt for PFHxS. The DOD doesn’t abide by these regulations.

Main Garrison Fire Station Complex

Building 4400 - Main Garrison Fire Station Complex

The Main Garrison Fire Station is located on General Jim Moore Boulevard between Lightfighter Drive and Gigling Road and includes a complex of three buildings. Building 4400 is currently operated by the Army as the Presidio of Monterey Fire Department, although it is owned by the City of Seaside.

The site is located at the southwestern edge of the California State University, Monterey Bay campus, south of the Otter Sports Complex. Land use near the site includes commercial properties, with a gas station, laundromat, restaurants, and retail space, owned and operated by the Army, as well as educational facilities owned and operated by the university.

Seaside Campus Town Project - The Red X is the site of the Burn Pit. The Blue X is the site of the Ord Military Community Fire Station, Building 4400. These sites are within a designated commercial center that is part of the larger Campus Town development.

Stormwater runoff from the front of Building 4400 flows north in a concrete channel parallel to General Jim Moore Boulevard and enters a depression at the intersection of Lightfighter Drive and General Jim Moore Boulevard.

AFFF concentrate was delivered to the Main Garrison Fire Station in 5- or 10-gallon plastic containers. Old or expired AFFF would periodically be rotated out of the tanks on the firefighting vehicles, with the old AFFF being discharged to the grassy area on the west side of Building 4401. AFFF tanks on fire department vehicles were also drained when repairs on the tanks were needed. Some AFFF could also have leaked or spilled in the grassy areas adjacent to the fire station during this activity.

Four existing groundwater monitoring wells downgradient of the Main Garrison Fire Station were tested, and a fifth well was drilled. All five groundwater wells sampled had detections of three or more PFAS compounds.

All 14 soil samples from the Main Garrison Fire Station had detections of one or more PFAS compounds; PFBA, PFHxA, PFOA, PFNA, PFBS, PFHxS, and PFOS were found in these soil samples.

Analytical results show that soils tested at 5 inches below the surface at the firehouse contained 2,990 parts per billion (ppb) of PFOS. These are dangerously high levels. Neither the EPA nor the state of California have established enforceable levels of PFOS in soil. As a result, public health may be at risk when the wind blows.

The Netherlands begins the regulatory process for PFOS in soil at .9 ug/kg or parts per billion, so the levels at the new Campus Town Center are 3,322 times above the Dutch threshold.

Neither the EPA nor the state of California have developed screening levels for PFAS in air or soil vapor. Workers at the fire station and others in the area may be at risk. There are no land use controls in place restricting access to or use of groundwater or soil at the Main Garrison Fire Station.

PFAS in Dust

Data from CDC PFAS exposure assessment, Martinsburg, West Virginia. “FOD” is the frequency of detection.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention examined PFAS in homes adjacent to the Shephard Field Air National Guard base in Martinsburg, West Virginia. Like Fort Ord, the base is highly contaminated with PFOS, PFHxS, and a host of other types of PFAS in soil and water. They found dust in homes outside the base at extraordinarily dangerous levels. PFOS was recorded at 13,900 parts per billion (13,900,000 ppt) while PFHxS was found in dust at 16,400 ppb.

PFOS is not considered volatile, meaning it does not easily evaporate into the air. However, it attaches to soil particles, eventually becoming part of the dust that settles in our lungs and homes.

The Army failed to test for the kinds of PFAS that are known to be highly volatile. They also failed to test homes for volatile organic compounds (VOCs) -- an egregious omission.

Vapor Intrusion

Denise Trabbic-Pointer, a chemical engineer who spent 42 years with DuPont, has been working with a team of scientists and medical doctors on Fort Ord’s contamination. They are deeply concerned with the Army’s lack of due diligence in its haste to unload poisoned lands to unsuspecting locals.

She explains, “With regard to volatile chemicals such as Trichloroethylene, Perchloroethylene, and Carbon Tetrachloride, aside from looking at groundwater contours and contaminant levels, the DoD and the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry have not performed vapor intrusion studies and/or a review of “Volatilization to the Indoor Air Pathways” (VIAP) inside residential homes at Fort Ord. The fact that there are no such studies where people actually live is a significant oversight and places all current and future residents in volatile organic compound-contaminated soil and groundwater areas of the former Fort Ord at risk.”

Fluorotelomer alcohols (FTOHs) are types of PFAS commonly found in aqueous film-forming foams (AFFF) and other military and industrial applications. Fluorotelomer alcohols are volatile organic compounds.

Unlike PFOS and PFOA, FTOHs have relatively high vapor pressures, allowing them to volatilize from water into air more easily. When groundwater is exposed to air, especially in sandy soils, Fluorotelomer alcohols can partition into the vapor phase to enter the air and people’s homes. In “partition” a compound tends to move from the phase where it is more concentrated to the phase where it is less concentrated until equilibrium is reached.

The Army failed to test for Fluorotelomer alcohols.

Vapor Intrusion is the process by which chemicals from contaminated soil or groundwater enter the indoor air of a building. The following diagram is from EPA’s Migration of Soil Vapors to Indoor Air.

The EPA has great information on these issues, but the agency does a poor job in enforcement, especially when it involves the DoD.

Per the Campus Town specific plan, future residential use is permitted but would be limited to levels above commercial spaces (second floor or higher). Is this protective of human health?

It's a good question.

Although the Army did not test the air in residential homes, they did test the air at the REI Outlet on Gen. Stilwell Drive in Marina and reported it contained 6.8 ug/m3 of the human carcinogen, trichloroethylene. That is 6.8 micrograms per cubic meter of air. This is 3.4 times the California action level for Trichloroethylene in indoor residential air. Are employees being notified? TCE action levels signal when steps should be taken to quickly reduce TCE exposure because of the possible short-term effects to unborn children. Women who work at REI who are pregnant or may become pregnant should be notified. Everyone ought to be notified.

The southeast corner of the REI Building contains 530 ug/m3 of the human carcinogen Perchloroethylene in the sub-slab of the floor. To test for volatile organic contaminants, workers drilled a small hole in the floor and installed an air valve in the hole. This way, they could collect an air sample from beneath the building for analysis.

The outdoor air is worse. The Army reported a frightening level of 970 ppb of Trichloroethylene in the air right outside of Michaels. They also reported 570 ppb of Perchloroethylene in the air in front of the Target store. It is critical that people understand the significance of these things.

See Figure 1 for more results: https://docs.fortordcleanup.com/ar_pdfs/AR-BW-2793/BW-2793.pdf

Former nozzle testing area near the Chartwell School

Historic amounts of carcinogen PFAS foams were sprayed here.

Fire department personnel conducted training, fire hose and tank flushing, and nozzle testing in a paved area near the Chartwell School on Numa Watson Road until the 1990s, before the property was transferred to the City of Seaside.

Fire department personnel were trained to perform nozzle testing with AFFF to ensure optimal flow and release of the AFFF mixture. Nozzle testing involved spraying AFFF through fire equipment. Fire equipment training also included arc training to maximize the arc, reach, and distance covered by AFFF in an emergency response.

Training took place about once a month for at least 10 years, releasing approximately 30 gallons of AFFF concentrate during each event. The nozzle testing area was a large asphalt parking area with storm drains that lead to channels that discharge into Monterey Bay.

Approximately 3,600 gallons of AFFF concentrate was used here. Usually, firefighters mixed 3% concentrate with 97% water. A single event using 30 gallons would be mixed with 970 gallons of water to produce 1,000 gallons of foam.

On August 19, 2024, in one of the greatest PFAS accidents in the nation’s history, 1,450 gallons of PFAS-AFFF concentrate spilled from Hangar 4 at the former Brunswick, Maine Naval Air Station. In November 2022, there was another historic release of approximately 1,300 gallons of AFFF concentrate at the Red Hill Bulk Fuel Storage Facility at Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam.

These historic releases don’t match the cumulative tragedy on Numa Watson Road.

Site 10 - Former burn pit

The Site 10 Burn Pit is shown at the corner of Gigling Road and General Jim Moore Blvd. Fire Station Building 4400 is shown on the east side of Gen. Jim Moore Blvd.

Site 10 is located near the main gate, about 160 feet south of the Main Garrison Fire Station. The site is near the intersection of Gigling Road and General Jim Moore Boulevard

The pit was approximately 45 feet long, 24 feet wide, and 2 feet deep. The site is unfenced and subject to vehicular and pedestrian traffic.

During fire suppression training, the burn pit was filled with 3 to 4 inches of water and fuel, ignited, and extinguished using AFFF with PFAS. Fuels used for this purpose reportedly included off-specification aviation fuel (JP-4), gasoline, diesel, and waste oil.

After the training sessions, water and residual unburned fuel percolated into the soil at the bottom of the unlined burn pit. AFFF was used regularly, from 1972 until 1991.

In 1995 the Army excavated an area approximately 80 feet wide by 100 feet long to a maximum depth of 10 feet. 1,451 cubic yards of soil were removed and treated at the Fort Ord Soil Treatment Area (FOSTA). I will return to this later.

The former burn pit and the Ord Military Community (OMC) Fire Station are within the Campus Town Project. These locations, and others within the lands acquired from the Army, are highly contaminated with PFAS.

A story by the Monterey Herald on the development of the Campus Town Project reported, “The work generally consists of decontamination, demolition, removal, and proper disposal of select buildings, structures, parking lots, improvements, and select trees, shrubs, bushes, and vegetation.”

What are the specific plans regarding “decontamination” and “proper disposal” of these materials? It’s another good question because decontamination of PFAS at the burn pit would be practically impossible.

The Army claims, “Human exposure pathways are considered incomplete, and Site 10 is recommended for SEA (Site Evaluation Accomplished) for both soil and groundwater.” In other words, the Army is saying the past use of these chemicals at this location won’t hurt anyone.

And there are no land use controls in place restricting access to or use of soil and groundwater at the old burn pit. This is damnable, horrendous public policy.

Groundwater testing

A groundwater sample taken 295 feet below the ground showed these levels of PFAS, in parts per trillion:

PFBA 20.8

PFPeA 52.4

PFHxA 98.0

PFOA 6.8

PFBS 43.9

PFPeS 30.3

PFHxS 16.8

Total 269.0 ppt

This is just one snapshot. The PFAS levels could be higher, depending upon the depth. It’s a shell game. Try to imagine the contamination from nearly 20 years of repeated use of thousands of gallons of aqueous film-forming foam.

The Army likely has a record of exactly how much AFFF concentrate they used at this location and most of the others throughout the base. There is a lot they are not telling us.

We can’t incinerate these chemicals, and we can’t spread them on farm fields or send them to the landfill. They take forever to break down. We don’t know what to do with them. It is truly frightening.

The Fort Ord Soil Treatment Area (FOSTA)

The Fort Ord Soil Treatment Area (FOSTA) was located at Site 20 shown here. It is located north of the intersection of Gen. Jim Moore Blvd and Lightfighter Drive. Today it is largely comprised of athletic fields on the campus of California State University Monterey Bay including Cardinale Stadium (formerly Freeman Stadium), home of the Monterey Bay Football Club.

FOSTA served as a facility for storing and treating contaminated soil. Active from 1995 to 1997, immediately after the base closed, highly contaminated soils were transported to this area, stockpiled, and “treated,” (although there is no method to render PFAS harmless.)

The red area shows the Fort Ord Soil Treatment Area. The California State University, Monterey Bay may be contaminated with hazardous materials.

FOSTA is profoundly impacted with PFAS. Chemicals treated included heavy metals at training ranges and volatile organic compounds, and petroleum hydrocarbons at maintenance yards, burn pits, landfills, and the wastewater treatment plant. Petroleum hydrocarbon-impacted soils were treated there as well.

The Army employed bioremediation, a method that utilized biological processes to degrade petroleum hydrocarbons present in the soil. PFAS may have been present in the excavated soils and bioremediation activities could have caused downward leaching of PFAS to groundwater. The Army also employed Soil Vapor Extraction (SVE) at the FOSTA to remediate soils contaminated with volatile organic compounds.

Fritzsche Army Airfield Fire Drill Area

The intersection of Imjin Parkway and Reservation Road is shown here, a little below the center of the figure. AFFF was used at the Fire Drill Area, the Fire & Rescue Station, and the Helicopter Defueling Area.

The former Fritzsche Army Airfield Fire Drill Area is located in the western part of the Fritzsche Army Airfield.

The former fire drill area was circular, with an approximate 100-foot diameter. The site is located in a low point surrounded by hills, so stormwater runoff offsite is unlikely.

The fire drill area was operated by the Army from 1962 to 1985. AFFF-containing PFAS was introduced in 1972. This area is currently owned by the Army and will be transferred to the University of California Natural Reserve System.

The use of the A-Aquifer for drinking water is prohibited here.

These results are from groundwater 105.2 feet below the ground. Though it is off-limits for drinking, this groundwater can slowly migrate and eventually discharge into streams, springs, or wetlands.

As part of training activities, waste fuel, primarily composed of outdated jet fuel, was discharged from an on-site storage tank into a pit, ignited, and then extinguished with the carcinogenic AFFF foams. Other fuels were used as well, including hydraulic and lubrication oils, gasoline, diesel, and solvents.

Training occurred at least four times per year with 100 to 200 gallons of AFFF being used during each training event. The Army says contamination was limited to the A-Aquifer, which is not used for drinking water purposes. They say there is nothing to be concerned about because a land use control prohibits installation of wells and use of the A-Aquifer for drinking water. However, there is more to the story.

Soil

Army fire drill areas are known to contain some of the deadliest contaminants known. They may contain volatile organic compounds (VOCs) like Benzene and Toluene. Lead, Mercury, Cadmium, Chromium (VI) and Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) may be found in the soils.

Treatment of these areas often involved removing thousands of cubic yards and moving them to another site.

In soil, PFOS was recently detected at 11,600 parts per trillion (ppt) and PFHxS was reported at 3,600 ppt at a depth of 68.8 feet. Eight additional PFAS compounds were detected at this depth. There are no restrictions on the use of soil in this area.

In 1987, approximately 4,000 cubic yards of contaminated soil were removed from the former fire drill area to a depth of 31 feet. The area was then backfilled with clean soil. Excavated soils contaminated with PFAS were spread over the area of the former fire drill to a depth of 2.5 to 3 feet above the original ground surface.

At this time, the Army was not paying attention to PFAS. In essence, they simply excavated the most seriously PFAS-impacted soils at the burn pit and distributed it throughout the area

A remediation risk assessment conducted in 1993 indicated chemicals remaining in soil at the former fire drill area did not present an unacceptable risk to human health or the environment per EPA exposure guidelines/limits and no further remedial action was necessary. On the contrary, further assessment and remediation is urgently needed.

Groundwater

Groundwater remediation using “pump and treat“ systems and groundwater monitoring was conducted from 1988 through 2014, before the Army began to treat for PFAS.

A “pump and treat” system is a common groundwater remediation technology used to remove contaminants from polluted groundwater. It involves pumping contaminated water from underground and then treating it above ground before either re-injecting it, discharging it to surface water, or using it for other purposes like agricultural irrigation.

Critics have compared this technology to taking a watermelon the size of an aircraft carrier, jabbing a couple of drinking water straws into the watermelon, extracting the water, treating the water with a less-than-proven scientific method, and then re-inserting the liquid into the watermelon and claiming everything is cleaned up.

“Pump and treat” works well in sandy soils but not in soils with clay or silt where contaminants can be trapped and slowly released over time, requiring decades to clean up effectively. Even after years of pumping, VOC concentrations can rebound as contaminants diffuse from low-permeability zones back into the groundwater.

The “treated” water from the fire drill area was discharged at different locations nearby.

“Treated” water discharge facilities on base included:

Two infiltration trench areas in the Fort Ord Nature Reserve.

One infiltration basin in the Off-Post Area Armstrong Ranch to the northwest of the Fort Ord Nature Reserve.

Two injection wells in the Fort Ord Nature Reserve.

A spray irrigation system in the former FAAF Fire Drill Area.

Fort Ord Nature Reserve - Red lines denote the reserve boundary. Blue lines are trails. Yellow lines are roads. The fire drill area is part of the nature reserve.

An infiltration trench is a shallow, excavated trench filled with gravel or other permeable materials designed to allow stormwater runoff to infiltrate into the soil. Instead of contributing to surface water and air/dust pollution, the water infiltrates into the groundwater. While effective for filtering some contaminants, infiltration trenches do not work well for PFAS.

An infiltration basin is a shallow, man-made depression designed to collect, temporarily store, and allow water to slowly infiltrate into the ground.

The infiltration basin northwest of the Marina Municipal Airport appears to be about 4,000 feet northeast of homes on Quebrada Del Mar Rd.

An injection well is a type of well used to place fluids deep underground. This method does not work well for PFAS chemicals. This method can isolate PFAS waste from surface water, air, and dust contamination, but this is not a long-term solution for PFAS contamination. There is a risk of migration into groundwater.

A spray irrigation system using waters known to contain PFAS should never be deployed. Spray irrigation may seriously threaten human health, especially when waters contaminated with PFAS is sprayed on land growing food crops.

Fritzsche Army Airfield Fire and Rescue Station

Soil boring operation at the Fritzsche Army Airfield Fire and Rescue Station. Photo taken 10/26/22.

The former Fritzsche Army Airfield Fire & Rescue Station is now City of Marina Fire Rescue Station #2 and is located at 3260 Imjin Parkway at the Marina Municipal Airport. The site was owned and operated by the Army as a fire station from 1961 through base closure in 1994. The City of Marina now owns the site.

AFFF was stored at the Main Garrison Fire Station in 5- or 10-gallon plastic containers and delivered to the Fire & Rescue Station to refill the tanks on firefighting vehicles on an as-needed basis. Old or expired AFFF would periodically be rotated out of the tanks on the firefighting vehicles, with the old AFFF being discharged to the grassy topographically low area south of the Fire & Rescue Station. This activity occurred approximately annually unless the AFFF tank on a vehicle had to be emptied for maintenance purposes, which occurred every several years.

Groundwater contamination at the former FAAF would have been limited to the A-Aquifer, which is not used for drinking water purposes.

Because long-term retention of longer-chain PFAS in shallow soils after extended percolation is possible, workers at the fire station could be at risk.

All 14 soil samples collected at the FAAF Fire & Rescue Station had detections of three or more PFAS, with detections of PFBA, PFHxA, PFOA, PFNA, PFBS, PFHxS, and PFOS in soil samples. In soil, PFOS was found at 17.1 parts per billion (ppb) at 1 foot. It was found at 203 ppb a mere 5 feet underground.

1H, 1H, 2H, 2H‐Perfluorodecane sulfonic acid (8:2 FTS) was reported at 13.1 ppb at 1 foot and 183 ppb at 5 feet down. So, what does this mean?

PFAS compounds like 8:2 FTS can adsorb to tiny soil particles. Adsorption is the adhesion to a surface. So, the 8:2 FTS can hitch a ride onto a tiny grain of soil which can travel into your lungs and your homes.

8:2 FTS has been associated with:

Kidney damage.

Thyroid dysfunction.

Reproductive and Developmental Toxicity

8:2 FTS degrades into PFOA, one of the most carcinogenic among all 16,000 PFAS compounds.

PFAS compounds like 8:2 FTS may travel through the air for many miles. We are in trouble.

Fritzsche Army Airfield sewage treatment plant

Specific details regarding the sewage disposal practices, such as whether wastewater was processed on-site or directed to a central treatment facility, are unknown. The sewage treatment plant was located in the northeastern portion of Fritzsche Army Airfield near the former Fort Ord boundary. It was operated from the 1950s until March, 1991 The plant treated wastewater from wash racks and maintenance shops at the Fritzsche Army Airfield and the nearby U.S. Army Reserve Center.

Sludge was never removed from the drying beds. This means concentrations could be extremely high here.

The sewage tank experienced overflows from the oil/water separators, and the evaporation ponds had cracks in the bottom, so it was possible for wastewater to percolate into the ground. The Army reports that soils had high concentrations of chlordane, cadmium, lead, and total petroleum hydrocarbons in the evaporation ponds. The Army removed soil from the location, but we don’t know where they put it.

PFAS used as a mist suppressant

The EPA lists Chromium-VI as being present at the Fritzsche Army Airfield. The Army won’t tell us precisely how this deadly carcinogen was used or how it was disposed of at Fort Ord. We do know how the military typically used it, and we know where it is present in the environment on base.

Chromium-VI was reported to be present at 15 sites on the former Fort Ord. Several are burn pits and sewer treatment plants, but some are machine shops. Treating metal with Chromium-VI strengthens metal and makes it more heat resistant, something important to a host of engines used by the military. Chromium-VI is also a corrosion inhibitor, applied to prevent rust and corrosion on metals, particularly in military equipment, aircraft, and heavy machinery. However, Chromium-VI fumes are deadly, and the military likely used PFOS as a Chromium-VI aerosol suppressant, adding it to the chrome baths to keep the fumes from escaping.

Erin Brockovich fought the use of Chromium-VI in Hinkley, California.

A chrome plating bath.

These locations at Fort Ord likely had chrome plating facilities. They may have used PFAS as a cleaner and degreaser:

Directorate of Logistics Automotive Yard, containing 8.5 fenced acres east of Highway 1 and northeast of the Southern Pacific Railroad Spur.

Site 14 (707th Maintenance Facility) occupied the southern half of the area bounded by North-South Road No. 2, North-South Road No. 3, and Gigling Road.

RI/FS Site 17 (1400 Block Motor Pool) was located within Fort Ord’s Main Garrison area. This site encompassed the motor pool complex—buildings numbered approximately 1476 through 1495).

IA Site 20 (South Parade Grounds, 3800 Block Motor Pool and 519th Motor Pool) were located in the southern portion of Fort Ord’s Main Garrison. This site encompassed the South Parade Grounds area.

Building T-4900

Building T-4900 served as the primary facility within the Directorate of Logistics Heavy Equipment Maintenance Yard. This yard’s northwest boundary was along the Fifth Avenue Cutoff. Nearby landmarks included Pete's Pond, a depression bordered by Eighth Street, and Fifth Avenue

Building T-4900 serviced fire department vehicles where flushing of tanks and systems containing AFFF may have occurred.

The facility included a concrete-paved wash rack where runoff discharged to an adjacent oil/water separator. It is suspected that fire department vehicle tanks would have been flushed at the wash rack and into the oil/water separator. Other liquids drained to Pete’s Pond.

The Army must be more transparent about the extent of contamination, and local residents, students, and business owners must demand answers

Site 40A – East Fritzsche Army Airfield Helicopter Defueling Area

Southeast side of Helicopter Defueling Area, facing east. Photo taken 3/5/21. The winds lift the carcinogenic dust and carry them into nearby residential neighborhoods.

The East Fritzsche Army Airfield Helicopter Defueling Area is located in the northwestern portion of the Fritzsche Army Airfield, east of the Fire & Rescue Station. The site was owned and operated by the Army until base closure in 1994. The site is now owned by the City of Marina and operated as part of the Marina Municipal Airport. The terrain is flat and sparsely vegetated.

Groundwater testing that was performed 99.5 feet below the surface showed dangerously high levels of PFAS.

PFOS alone was reported at 19,000 parts per trillion. This is 4,740 times over the EPA’s maximum contaminant level. The DoD dictates environmental policy in these matters.

Alarming levels of PFAS in the groundwater

at the Helicopter Defueling Area

A 24-inch diameter storm drain line runs through the helicopter parking apron east of the Fire & Rescue Station and parallels Imjin Road. This storm drain line discharges at an outfall approximately 450 feet east of the Fire & Rescue Station.

From there, the discharge travels via surface drainage to a topographically low area to the northeast of the helicopter parking apron. Surface runoff from the helicopter parking apron appears to have also drained to the same topographically low area.

Sometime in the late 1970s or early 1980s, a defueling tank ruptured in this area, and 5,000 to 10,000 gallons of fuel were spilled. The fire department applied AFFF to the spill area to reduce the likelihood of fire. After the spill was contained, soil was placed in the spill area to absorb the fuel (and AFFF), after which the soil was loaded into dump trucks and disposed of at an unknown location.

Local authorities must demand transparency and take steps to protect human health where these carcinogens were discarded.

Some AFFF entered the low area to the north of the site.

The Army says groundwater contamination at the former Fritzsche Army Airfield would have been limited to the A-Aquifer, which is not used for drinking water purposes. Groundwater wells sampled had detections of twelve or more PFAS compounds. Groundwater flow at Site 40A in the A-Aquifer in the area is toward the northeast.

The East Garrison Sewage Treatment Plant

The East Garrison Sewage Treatment Plant was built in the 1930’s and decommissioned in 1997. It was located near Reservation Road, north of Inter Garrison Road.

Treatment consisted of unlined sludge beds, an unlined percolation pond, and two concrete sedimentation tanks. The Army says there is no PFAS here because the East Garrison Treatment Plant only received wastewater from toilets and showers used at the East Garrison. However, residential use of water contributes to PFAS in the waste stream. For instance, washing a jacket coated with water repellant containing PFAS Can send high levels of PFAS down the drain. Residences may contribute heavy metals, pesticides, and petroleum hydrocarbons to the waste stream.

In 1997, the Army removed dried sewage sludge from the inactive drying beds, and soil containing elevated concentrations of metals, pesticides, and petroleum hydrocarbons.

The East Garrison area, including the sewage treatment plant, containing about 224 acres, was transferred in 2004 to the East Garrison Partners (EGP) for redevelopment. A new residential neighborhood was constructed over the area.

AFFF Fire Suppression Systems in Hangars

A fire suppression system with AFFF is tested at a military hangar.

The Army reported in 2022 that there was an accidental discharge of foam from the fire suppression system in either Hangar 507 or 527 at the Fritzsche Army Airfield. The accident resulted in more than five feet of foam covering the floor of the hangar. We know from the Preliminary Assessment Report in 2022 that these hangars were fitted with foams containing PFAS.

The same report documents interviews with site personnel indicating that one of the two hangars filled with three feet of water and a “very thin” layer of foam on top of the water. The report says this was likely not AFFF containing PFAS. This is difficult to believe because virtually all military hangars were fitted with AFFF systems.

Hangars with fire suppression systems at Fort Ord

Building 507

Building 510

Building 524

Building 527

Building 533

PFAS site inspections on Air Force and Navy bases conducted prior to 2020 went into great lengths detailing the history of accidents involving fire suppression systems at multiple hangars. Improper handling during system maintenance or training resulted in massive, unintended releases. Pipes, valves, and storage tanks degraded, leading to leaks. Power surges, electromagnetic interference, and sensor malfunctions can cause the system to go off. Heavy machinery, explosions, or accidental bumps to system components can cause rampant foaming.

AFFF fire suppression systems are responsible for the release of tremendous amounts of PFAS into the environment. The releases of AFFF during routine fire training practice and the use of PFAS in chrome plating baths may result in similar levels of releases.

It’s not too difficult to test soil and groundwater at these locations. It should be done immediately, especially when the entire terrain of the former base is rapidly transforming into residential and commercial developments with many vulnerable people.

Julie Akey

Julie Akey at Fort Ord in 1996.

Army veteran Julie Akey lived at Fort Ord in 1996 and1997 while studying at the Defense Language Institute for a year and a half. Julie was diagnosed in 2016 at the age of 46 with multiple myeloma, a rare blood cancer.

She set out to find others on the base who might be similarly afflicted, and she found 138 people diagnosed with the deadly blood cancer. Julie created a spreadsheet with demographic information and the diseases of almost 1,700 people who lived on base. (See it here.) This is a historic achievement.

Julie described her experience, “My time on the beautiful Fort Ord changed my life, but not for the better. In fact, I keep the database on people who are also sick from Fort Ord. Because of this, I encourage you to take this PFAS report seriously. Although Fort Ord has been “cleaned up,” the land and water is still polluted with PFAS and other contaminants. It’s still making people sick.”

She continued, “The base was “cleaned up” before any of us ever heard of PFAS. There is no mention of cleaning up any of the hundreds of chemicals that fall into the PFAS category. While we know a decent amount about the diseases caused by Trichloroethylene, (TCE), one of the biggest contaminants found on Fort Ord, and Agent Orange, the poison used to kill the ubiquitous poison oak on base, we are gradually learning about PFAS and the illnesses these chemicals cause. I hope this report will convince you to take a closer look at the PFAS and other contaminants that still remain in the land and water on the former Fort Ord. They are literally killing us.”

Recent history

Since Fort Ord closed in 1994, much of the original base is no longer owned by the Army and has been transferred to various public and private owners. The former Main Garrison area is now primarily owned and operated by California State University Monterey Bay (CSUMB), with some areas owned by Monterey Peninsula College, the City of Marina, and the City of Seaside.

In 1995, the Fritzsche Army Airfield was transferred to the City of Marina for use as the Marina Municipal Airport. Portions of the former Fort Ord between Reservation Road and the airport are now owned by the University of California and are operated as the University of California, Monterey Bay Education, Science, and Technology Center. The eastern part of the site is operated by the U.S. Bureau of Land Management as the Fort Ord National Monument.

The former East Garrison area is owned by Century Communities and is now operated as the East Garrison housing development. The Pacific Ocean beach portions of the former Fort Ord are now owned by the California Department of Parks and Recreation and are operated as the Fort Ord Dunes State Park. Much of the Inland Ranges, however, remain owned by the Army.

It’s important to know the land ownership history because neighborhoods built over the former base may be dangerously contaminated. Sickened plaintiffs will want to know who to sue. They can’t sue the Army because the Army will claim “sovereign immunity.” This concept of sovereign immunity is in vogue these days. It is derived from medieval notions that “the King can do no wrong.” In this case, it means the Army reserves the right to poison the public in the name of national security.

Fort Ord Reuse Authority, (FORA)

The map below was published by FORA on its way out the door. FORA was a governmental agency created in 1994 to oversee the transfer and redevelopment of the former Fort Ord. FORA was responsible for planning, financing, and implementing the transition of the contaminated Army base into civilian use. It ceased to exist in 2020.

FORA brought together multiple government agencies to collaborate on the redevelopment of Fort Ord. The voting members included representatives from these 8 jurisdictions:

County of Monterey

City of Marina

City of Seaside

City of Del Rey Oaks

City of Monterey

City of Sand City

City of Pacific Grove

City of Carmel-by-the-Sea

It was their responsibility to oversee environmental cleanup before properties were handed over to civilians. This is not something achievable with PFAS. These officials failed miserably. They share liability with the Army and the state of California for their collective failure to protect human health.

FORA left us this map and spreadsheet of the way things stood in 2020 when they exited the stage.

Can you help us pay for environmental testing on the former Fort Ord? We have raised $2,600 so far. Our goal is $20,000. Our team will visit in early October, 2025 to take samples. Please help us! See the Fort Ord Contamination website. https://www.fortordcontamination.org/

===================================

Sources

The Fort Ord Cleanup Administrative Record database contains over 10,000 records https://www.fortordcleanup.com/documents/search/

Fort Ord Locater Map

https://fora.org/Reports/fortordlocatormap.pdf

EPA Fort Ord Contaminant List

https://cumulis.epa.gov/supercpad/SiteProfiles/index.cfm?fuseaction=second.contams&id=0902783

July, 2023 - Site Inspection Narrative Report Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances Former Fort Ord, California U.S. Department of the Army Fort Ord Base Realignment and Closure https://docs.fortordcleanup.com/ar_pdfs/AR-BW-2942//BW-2942.pdf 14,395 pages

September 2022 - Preliminary Assessment Narrative Report Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances Former Fort Ord, California 309 pages

https://docs.fortordcleanup.com/ar_pdfs/AR-BW-2904B/BW-2904B.pdf

February, 2022 - FINAL PRELIMINARY ASSESSMENT OF PER- AND POLY FLUOROALKYL SUBSTANCES V2 Presidio of Monterey and Ord Military Community, California 33 pages

https://aec.army.mil/Portals/115/PFAS/POM_PASI.pdf?ver=50d44b8fvCrh6O006dqqPQ%3D%3D

February, 2020 - Technical Summary Report - OU 2 - Perfluorooctanoic Acid and Perfluorooctane Sulfonate Basewide Review of Historical Activities and Groundwater Monitoring at Operable Unit 2 Former Fort Ord, California, 1,345 pages https://docs.fortordcleanup.com/ar_pdfs/AR-OU2-722A/OU2-722A.pdf

February, 2004 - Final Source Evaluation Report Former Fort Ord – California Regional Water Quality Control Board 18 pages

https://docs.fortordcleanup.com/ar_pdfs/AR-BW-2292A/BW-2292A.pdf

June, 1992 - Fort Ord Community Task Force Strategy Report, 712 pages

https://www.fora.org/Reports/1992-06-19_Ft_Ord_Comm_TF__Strategy.pdf